I am William

William Colenso

1811-1899

I am William

William Colenso

1811-1899

Hapu

Colenso clan

Iwi

Cornish/English

Mahi (Work)

Printer, Missionary – Church Missionary Society/Anglican, explorer, naturalist, politician

Tell us about your early life…

I was born and raised in the town of Penzance, Cornwall, in the south-west corner of England. My father was a town councillor and earned his living making and repairing saddles for horses. My mother was the daughter of a solicitor. I was educated by a local tutor and then learnt the craft of printing.

It was printing that took me to New Zealand. The Church Missionary Society needed a printer to operate their small press at Paihia. I arrived at the Paihia mission settlement at the close of the year 1834.

What were your life’s achievements?…

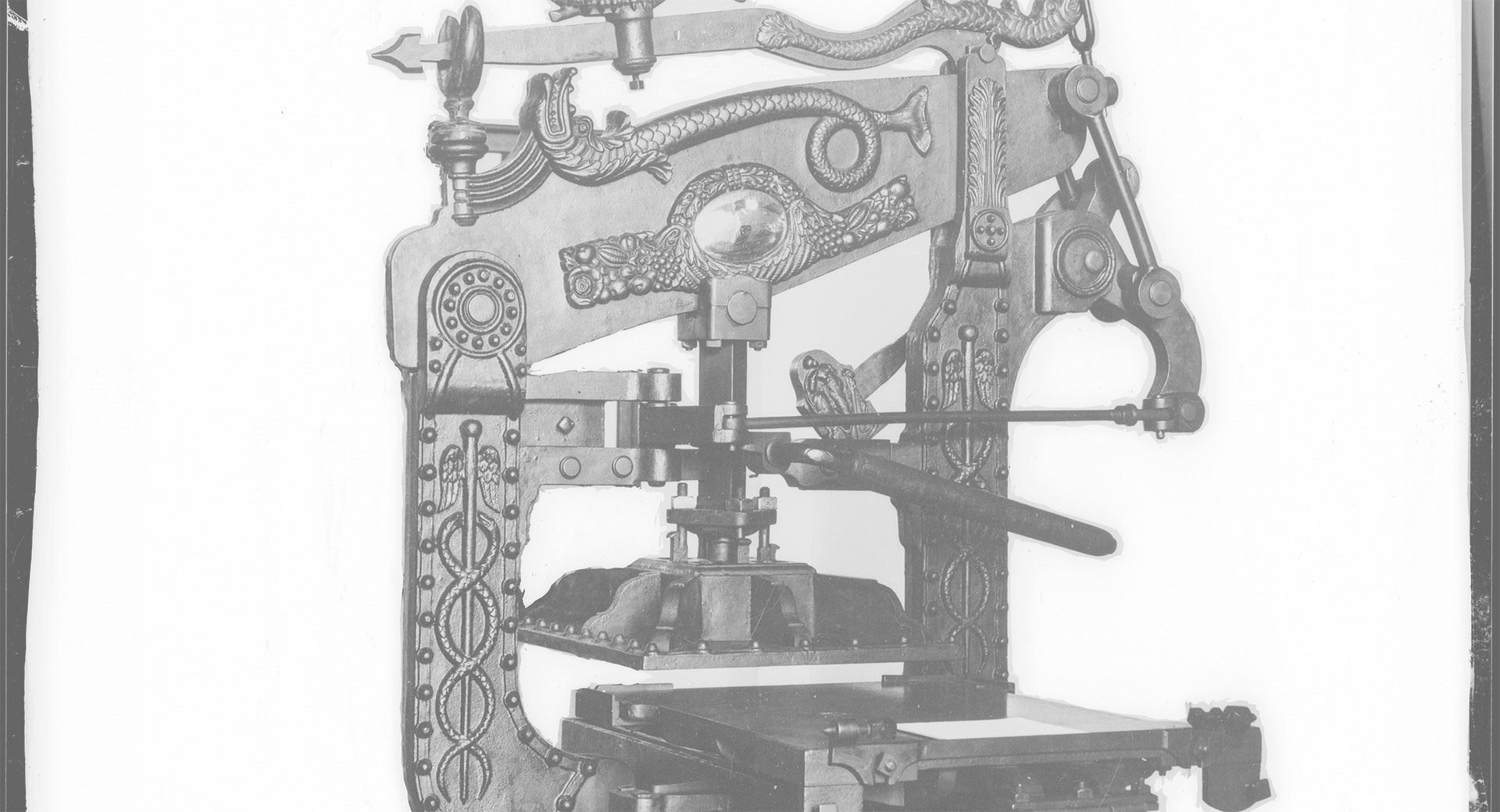

My early years in New Zealand were consumed with the task of printing translations of the Bible and Prayer Book in the native tongue (te reo Māori). In 1837, on a small Stanhope press and with inadequate equipment, I printed 5000 copies of the New Testament. I printed various other books of the New Testament and Old Testament in the late 1830s and early 1840s, including the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Isaiah (the last translated by Robert Maunsell).

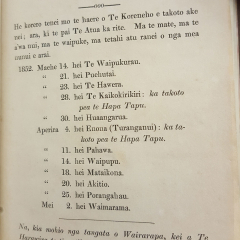

The greatest number of volumes by far that I printed at the Paihia press were those of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP). The BCP had been central to Anglican worship since the Reformation. In total, I printed around 53,000 of these in the period 1835-42. (I recorded all these printing figures in my Ledger; an image of this is included below.)

In these years, Māori unceasingly requested copies of the Bible and Prayer Book – they called the latter Te Rawiri, after the Psalms of David (‘Rawiri’) that were included in it.

I also printed the Māori text of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 and in the years following. Henry Williams had hundreds of copies printed for distribution, during the Hone Heke flag-staff crisis, to reassure Māori of the Crown’s benevolent intentions.

For myself, I always had some doubts about those intentions (although I reckon my mission colleagues believed the British Crown was the best chance of security for native rights). Some of these doubts were reflected in my diary account of the Waitangi treaty signing that was printed only in 1890, some fifty years after the fact. (I understand this account has since become relied on by historians to retell the story of the treaty signing at Waitangi.)

I explored Waikaremoana and the Urewera region in 1841-42. From October 1843-44, I explored from Wairarapa to Ahuriri (Hawke’s Bay) and settled on the site for a new mission station. We landed on the Wairarapa Coast (at Castlepoint) and then trekked north with local Māori guiding us.

My interest in collecting botanical specimens lead to various publications in the Transactions of the New Zealand Institute, and I was eventually elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Toughest challenge?…

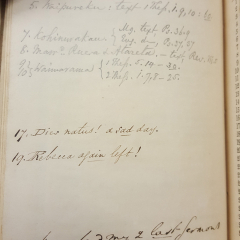

I cannot deny that I struggled in my marriage to Elizabeth, daughter of the missionary, W. T. Fairburn; I then fell for a young native woman, Rīpeka, who was a member of my household. Consequently, in 1852, I was suspended as a deacon and dismissed from the CMS. I never saw my wife and daughter again.

I obviously failed my wife, who was a gifted woman and linguist in her own right. I believe that I also loved Rebecca (Rīpeka), and we had a child together – Wiremu (William). For a few years following these incidents, I was quite alone in the world, with scarcely any friends or confidants.

However, I recovered myself and served many years as a representative for Napier Town on the Hawke’s Bay Provincial Council. Between 1861-66, I was also the M.P. for Napier. In the final years of my life I regained my position as a deacon and was readmitted to the Anglican clergy.

What is your closing message for us?…

Perhaps it was something to do with my upbringing – the son of a town councillor and grandson of a solicitor – but I always believed in making my voice heard in a right cause. This sometimes earned me friends, but often I made enemies. I was unpopular with sections of the local settler population throughout my life. My appeal for clemency in the case of Kereopa Te Rau (hung at Napier, January 1872, for the murder of Volkner) provoked the ire of many. For myself, I was inspired by the words of one philosopher king:

‘Open thy mouth for the dumb in the cause of all such as are appointed to destruction.’

‘Open thy mouth, judge righteously, and plead the cause of the poor and needy.’

(Proverbs 31: 8-9)

REFERENCES

William Colenso, diary/maramataka 1852, MSX-5196, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

William Colenso, printing ledger, Paihia press, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

William Colenso, The Authentic and Genuine History of the Signing of the Treaty of Waitangi (Christchurch, 1984 (1890)).

David Mackay, ‘Colenso, William’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1990, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1c23/colenso-william (accessed 2 November 2020).

Steven Oliver, ‘Te Rau, Kereopa’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1990, updated June, 2014, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1t72/te-rau-kereopa (accessed 16 November 2020).

Trevor Ulyatt, Photograph of the Columbian printing press formerly owned by William Colenso, Ref: 1/2-050378-F, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

Written by S. Carpenter. © Karuwhā Trust 2020

Note: this interview style ‘autobiography’ has been written based on historical data and all quotations are from actual archival documentation or (occasionally) family oral tradition; artistic or interpretive license has of course been taken with the style or ‘voice’ of the subject person. References are given for further reading and research purposes.

Hone Heke

“I was born at Pākaraka, near the maunga Pouērua, inland from Pēwhairangi – what the Pākehā call the Bay of Islands. I was given the name Pōkai after my mother’s brother...”

Read more

Henry Williams

“I was born in 1792, in Gosport, south England, near Britain’s main naval base at Portsmouth. My parents were Thomas Williams, a hosiery merchant, and Mary...”

Read more

Rāwiri Taiwhanga

"I do not know when I was born in terms of the years since our Lord’s birth “A.D.”. When I died in the 1870s, however, some Pākehā thought I was 100 years old..."

Read more